| Issue 1, Winter 2003 | ||||||

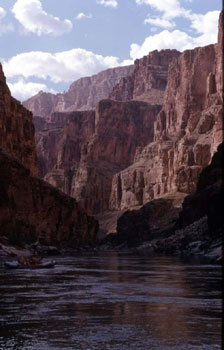

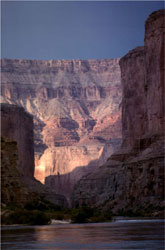

In Depth: A Wilderness Riverby Kim Crumbo

The National Park Service is currently revising its Colorado River Management Plan (CRMP) for the Colorado River as it flows through Grand Canyon National Park. Two critical issues—wilderness protection and non-commercial access—must be addressed to better protect the river’s natural character. Congress passed the Wilderness Act in 1964— In order to assure that an increasing population, accompanied by expanding settlement and growing mechanization, does not occupy and modify all areas within the United States...leaving no lands designated for preservation and protection in their natural condition... Only an act of Congress can actually designate a wilderness area. While this hasn't happened yet at the Grand Canyon, National Park Service policy requires that "proposed" wilderness areas be managed the same as officially designated wilderness, with the expectation of eventual wilderness designation (USDI 1999, Section 6.3.1).

The most obvious benefit of wilderness rests in the prohibition of development, including roads, administrative or commercial buildings, power lines, suspension bridges, cable cars, and the like. A second wilderness benefit, the mandate to provide "outstanding opportunities for solitude and a primitive and unconfined type of recreation," is often referred to as the "wilderness experience." Within wilderness, the managing federal agency is required to provide recreational opportunities by first protecting the area’s ecological integrity and secondly limiting, when necessary, the frequency of encounters between individuals and groups.

On a river, this can be accomplished through group size and launch limits grounded in ecological and social science research. This approach allows the individual to derive her or his river experience based on an intact ecosystem free from crowds. After the Wilderness Act was passed in 1964, visitor numbers on the Colorado River burgeoned from about 550 people annually to nearly 10,000 in 1970. The Park Service recognized the need for new regulations to counteract the resulting degradation and embarked on a two and a half-million dollar, 10-year long river-wilderness planning effort (USDI 1970:8; 1980). In 1980, the Park Service produced a plan that conformed to wilderness experiential and ecological standards by spreading out most river use over six months, reducing group size, and phasing out motors. Motors are prohibited by the Wilderness Act (Section 4(c)). The 1980 plan also increased the commercial allocation by about 18 percent in order to facilitate the transition from motors to oars. In response, river-running concessionaires convinced Senator Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) to insert an amendment to the 1981 Department of Interior appropriation bill that withheld funds necessary to implement the 1980 river plan. Although the funding restriction applied only for 1981, the Park Service's upper echelons disregarded the Wilderness Act, its own regulations and policies, ecological and experiential protection, and extensive public involvement. The result was a new river plan in 1981 that institutionalized crowding and congestion, increased river use and motors, and avoided hard decisions that could prevent ecological impacts from dam operations and recreational use.

Today, the non-commercial, "do-it-yourself" river runners have a 20-year waiting list to get a trip, and large groups, dam operations, motorboats, and helicopter businesses continue to impact the canyon's ecological and experiential aspects. Although most conservationists' concerns lie with continued impacts to the canyon's ecological and wilderness values, the overriding concern for the $29 million-a-year river running industry is the prospect of phasing out motors.

Although most conservationists' concerns lie with continued impacts to the canyon's ecological and wilderness values, the overriding concern for the $29 million-a-year river running industry is the prospect of phasing out motors. In a recent issue of Boatmans’ Quarterly Review, the publication for the Grand Canyon River Guides Association, concessionaire spokesperson Mark Grisham states that wilderness advocates endorse substantial reductions in commercial use. Neither the Grand Canyon Wilderness Alliance, which represents five million members, the Arizona Wilderness Coalition, nor the Sierra Club has endorsed any such proposal. Diminishing recreational impacts through the reduction of group size limits, staggered trips, and the phase-out of motors will achieve wilderness protection goals without reducing the number of visitors that are able to enjoy the river (see "Wilderness and the End of Guiding," Volume 13, No.1). The current river management planning process allows us the opportunity to explore a range of alternatives regarding ecological protection and access issues.

Grisham further asserts "motorized trips are the principal reason why Grand Canyon river trips are accessible to a very broad range of the general public, from young children to the elderly, to those with even severe disabilities...." In reality, professionally guided trips—oar or motor—provide access to those who don't know how to run the river but can afford a guided trip’s cost. Commercial trips are expensive, affordable principally to society's upper income levels. For example, about 50 percent of river passengers surveyed make over $100,000 a year, an economic elite representing about eight percent of American society (Hall and Shelby 2000; Jonas 2002). Suggestions that commercial trips, motor or otherwise, provide "greater and broader public access" are disingenuous at best. Real opportunities exist for expanding river access to disenfranchised publics (see Crumbo 1998), but the industry has yet to seriously promote access improvements for these groups. Wilderness designation for the Colorado River would assure the highest level of protection of the canyon's ecological and experiential treasures and would provide opportunities for the broadest range of access for the American public. Kim Crumbo has worked professionally as a river guide, river ranger, and wilderness manager at Grand Canyon for over 30 years. He is currently the Grand Canyon Regional Coordinator for the Arizona Wilderness Coalition. |

||||||

Make your late winter and early spring outdoor plans here! Visit our comprehensive list of day outings, inventory trips, meetings, and upcoming AWC events for the latest in wilderness “happenings” around the state.

Make your late winter and early spring outdoor plans here! Visit our comprehensive list of day outings, inventory trips, meetings, and upcoming AWC events for the latest in wilderness “happenings” around the state.